Daniel Stein and American Cartoonist Keith Knight, creator of The K Chronicles, (Th)ink, and The Knight Life, discuss the racial politics behind recent cases of American police brutality such as the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO. Their conversation centers on the political potential of cartoons and comic strips and on the role of the cartoonist as a cultural commentator.

Daniel Stein and American Cartoonist Keith Knight, creator of The K Chronicles, (Th)ink, and The Knight Life, discuss the racial politics behind recent cases of American police brutality such as the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO. Their conversation centers on the political potential of cartoons and comic strips and on the role of the cartoonist as a cultural commentator.

In Keith Knight’s comics and cartoons, racial conflicts and the peculiar experience of the African American community have always been central themes. “I was writing about racism long before I was making fun of presidents,” he noted in an interview we did a few years ago [see Stein 2011]. Whether it’s his longest-running autobiographical strip The K Chronicles, his nationally syndicated daily strip The Knight Life, or his single-panel cartoon (Th)ink, Knight invests his take on the ironies and absurdities of living in contemporary America with a keen sense of personal insight and a broad spectrum of humor ranging from visual slapstick and verbal puns to full-blown satire. Even though he often tells his audiences that the bulk of his material has a positive rather than an angry slant (an assessment that is certainly true), some of his most controversial and most poignant work attacks the status quo of American race relations.

One major bone of contention in Knight’s work is the continuing prevalence of police brutality, which looms large in African American history. Think, for instance, of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, and especially of the police response to the non-violent protests in Selma, Alabama, on March 7, 1965, when peaceful protesters were attacked by police forces as they were crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge. For Knight, who was born about a year after the Selma protests (which went down in history as “Bloody Sunday” and were just recently brought to the big screen in Ava DuVernay’s critically acclaimed 2014 film Selma; they are also featured prominently in John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell’s March: Book One, published in 2013), the issue of police brutality first came into focus in the wake of the Rodney King beatings by the LAPD and the LA riots that followed in response to the policemen’s acquittal in 1992. Later in the decade, in 1999, Knight did a K Chronicles strip about the killing of Amadou Diallo by the NYPD, a case that caused a public outcry over the use of excessive force by the policemen and found its way into popular culture through Bruce Springsteen’s “American Skin (41 Shots).” Picking up on the policemen’s claim that they had shot Diallo in self-defense (a claim the courts actually believed), the strip shows a young black kid asking, “Mr. white police officer … How many shots does it take for four white officers to defend themselves against one unarmed black male?” The answer unfolds over the next six panels, with the word “Blam!” extending forty-one times across the page, thereby making a very serious point through the sequentiality of the comic strip: what may or may not have started as an ill-advised attempt at self-defense by New York police officers, who may have felt threatened by a black man whom they may have believed to be armed (but who turned out not to have been), eventually–at some moment within these six panels–turned into an act of murder. But the strip doesn’t end there. Knight adds two final panels, the first of which shows the kid asking the cop, “don’t you think that was a little excessive,” while the second delivers the racially inflected punch line through the cop’s claim: “Listen … You people could avoid getting into these situations if you would just lighten up!!” Here, then, the visual critique presented in the previous panels gives way a verbal twist that reveals Knight’s penchant for politically poignant humor as well as his knack for satire [On the black politics of Knight’s work, see Stein 2012].

Since the 1990s, Knight has devoted many comics and cartoons to the victims of American police brutality (Oscar Grant, Amadou Diallo, Michael Brown, and many others). He also keeps updating his K Chronicles strip “Gravestones and Nightsticks,” which memorializes these victims by placing their names on gravestones while simultaneously lambasting police forces around the United States for killing innocent people, in the kind of gritty humor that informs much of his work. When the black teenager Michael Brown, a resident of Ferguson, Missouri, was shot and killed by the white police officer Darren Wilson, on August 9, 2014, it caused weeks of massive protests and a heated national debate about what many had hoped would be a ‘post-racial’ era in which the aftereffects of slavery and racial discrimination would finally be put to rest. Knight decided to devote a whole slideshow to the issue at hand: a slideshow that would feature his many years’ worth of strips about police brutality and would combine these strips with personal reflections on living as a black man in America. He contacted me with the idea of taking this slideshow to Germany, a country he visits quite frequently. He had already done a mini-tour through Germany in 2011, where he talked about his work at the Universities of Göttingen, Osnabrück, and Bochum. This time around, we were able to set up a few more presentations, and so, between Nov. 17 and Nov. 25, 2014, Knight brought his slideshow to the Universities of Siegen, Bremen, Osnabrück, Bochum, and to the FU Berlin. I attended the shows in Siegen and Berlin, and Keith kindly agreed to meet for an interview the morning after his presentation in Siegen. What follows is a revised version of that conversation, a text that began with the transcript of our interview and then evolved into a longer edited text based on our email exchange after the tour. Also included are some of Keith’s answers to questions from the audiences in Siegen and Berlin. The interview is structured into three sections: Race and the Politics of Police Brutality; Comic Strips and Cartooning; Looking Forward, Making Change.

Race and the Politics of Police Brutality

DS: In the strip you did to announce your German slideshow presentation tour, you said you had talked to some relatives who are police officers as well as to other people on the police force. What did they tell you?

Fig. 1. Keith Knight, “They Shoot Black People, Don’t They?”

KK: One of the former cops I talked to said that if there was a bad cop and they didn’t want him involved in an incident, they would put him in a 7/11 parking lot with a coffee and a donut and just say, “You don’t have to come on this one. Just stay where you’re at. We’ll take care of this one.” That’s funny, but it doesn’t solve the overall issue that there’s a crappy cop and that you’re not really getting rid of him. I think that’s a big downer. You know, there need to be outside investigators. One former cop I talked to said that they tried that, and a lot of the cops said, “I’m not going to police then, I’m not going to do my job then.” But you know, too bad, they should lose their jobs if they react that way. There’s plenty more new cops coming up. People always say, “This is such a hard job; it needs to be held to a higher standard.” Yes, it does. But there also need to be higher quality people in it. You need to weed out the bad cops. Because every bad cop is a stain on the police force; every bad cop sticks out like a sore thumb, is worth five good cops. Of course, there are fine police officers out there. It’s just that even when you’re a good police officer, if you’re not playing the game with some of these police officers, they will not help you. There were cops interviewed in New York about this whole stop-and-frisk policy, and when they weren’t doing enough stopping of black and brown people, they got called in and were told, “You’ve got to get your crime stats up. If you don’t get your numbers up, we’re going to stick you in the worst part of town.”

DS: Have you talked to any black cops? Do they have a different perspective?

KK: Yes, there are black cops out there, but merely diversifying the police department isn’t going to solve everything. I’ve run into black cops who act worse than white cops because they want to prove to the white cops that they are on their side. The first time I jaywalked in LA–you’re not supposed to jaywalk in LA, but I’m from Boston, and we run across the street so we don’t get hit–so I walked across the street in LA and this black cop was like, “Hey, you think I’m an asshole?” He was completely obnoxious. I felt like saying, “There’s no other cops around, you don’t have to show off for them,” but that would have gotten me into trouble. Anyway, there are cops who are complete jerks, and then there are cops who are not complete jerks. Hopefully, more of them are not complete jerks. But police departments do need to become more diversified and reflect the community. If you can get cops who are from the community, things like Ferguson would not happen. Darren Wilson,the cop who shot Michael Brown, would have known him and could have just said, “Hey, what’s going on, what are you doing? Could you just walk on the sidewalk?” It would have been a simple thing that would have changed everything.

DS: What do you think makes American cops so trigger-happy?

KK: First, because they know they can get away with it. Second, many people in America grow up without having relationships with people who don’t look like them. So they get this us-versus-them mentality. Cops need to spend more time in the community, doing more than just policing. There need to be outreach programs. Third, it’s the gun culture. Cops are just super paranoid, but they don’t need to be paranoid. You hear a lot of people arguing on Fox News, “Police brutality isn’t the problem; black-on-black crime is the problem.” Here’s the thing: black people shoot black people and white people shoot white people at practically the same percentages. You could say, “The problem is white-on-white crime.” But they like to deflect the blame. It’s the police’s job to serve and protect me. My taxes pay for their salaries; my taxes pay for when someone sues the police department for killing their kid. You know, I’m more fearful of the police cruising by outside of my place than of anybody else.

DS: I read quite a bit of the news coverage of the Ferguson riots, and one argument many analysts made was that there was some kind of disconnect between the police and the people, and that part of this disconnect came from the fact that the town’s demographics had undergone rather rapid change. Ferguson used to be predominantly white not too long ago, and now it’s predominantly African American. But the institutions haven’t shifted. You still have a predominantly white police force, and that creates tensions.

KK: Sure, but who is going to know this demographic shift better than the police force that cruises through there? They should be the first to be on top of that. One of the points I missed during my slideshow yesterday is that, instead of allowing police departments to pay out people, I think we need to hit them in the wallet. They continue to do this without impunity because they don’t get punished at all. They feel like they’re completely protected. The worst that’s going to happen is that they lose their job and they get a job somewhere else. But if their pensions are hit, and not only the cop who does it, but the cops they work with, and the precinct, then there will be people looking out for each other, being like, “Hey, take it easy. I have a family to feed, and that type of thing.” The cops I’ve talked to agreed with me on that.

DS: Gun culture might be part of the problem. In the United States, especially in places with concealed weapon laws, a cop who stops a random car on the freeway has to assume that the driver has a firearm. That makes any routine traffic stop a potentially dangerous situation.

KK: Yeah. Many people argue that if you take away people’s guns, only the bad guys will have guns. Okay. Well, all right. Let the police and just the bad guys have guns. It would be easier for them to deal with it instead of every Tom, Dick, and Harry having a gun, or every policeman thinking that every Tom, Dick, and Harry had a gun. Maybe the cops should become the advocates of gun control. Maybe they should say that guns shouldn’t be available to everybody. See what happens. I think the right-wingers would freak out and their heads would explode. I like to see that, too. But if you think about the shooting of Amadou Diallo, I wonder at what point did it go from defense to offense? Because that was the cops’ justification: “We were trying to protect ourselves.” And that’s the problem. A cop can always say, “I thought I saw a shotgun. I thought he had a gun, I thought she had a gun.” I’m sorry, but it’s not about protecting the cop, it’s about protecting the neighborhood, protecting the people. As a cop, you are a servant. That’s the risk you take when you take on the job.

DS: It’s not just the question of when it goes from defense to offense. If four cops were taking shots at Amadou Diallo 41 times, it’s also the question of how much pleasure did they get from shooting somebody who is already dead or at least severely injured. What makes you point the gun to the floor and keep shooting at this already incapacitated person?

KK: I didn’t even mention Eric Garner during my presentation, the guy who was supposedly illegally selling individual cigarettes in New York outside of a bodega. One cop ended up choking him to death–over cigarettes! The guy put him in an illegal chokehold, and Garner was going, “I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe!” There were all these other cops around them, and no one was saying, “Let up on this guy!” It’s all on video. Everything is quiet right now, because there is no story that the cops can come up with because it’s all right there on tape. So I don’t know what’s going to happen to these cops. They might get fired. The police department will probably get sued. But nothing will really change.

DS: It’s also not just about that individual cop who did the choking. Police departments should think about what new procedures they would have to implement so that these things will not happen again.

KK: Yeah, that’s the thing. You’ve got to hold the precinct accountable. Because too many times, they get the low-rung guy although you know that the people on top totally advocate it. And you know it’s not the first time it’s happened, it’s just the first time it got caught on tape.

DS: You talked about possible solutions in your presentation. It seems that you suggested that things have to be fixed on the grassroots level, between the local police and the community. Do you think it has to be a bottom-up solution, especially since the Republicans gained so many conservative votes in the recent midterm elections, and also considering the growing distrust in political institutions regardless of which party is in charge at the moment?

KK: Midterms are always a chance for the Republicans to pass all these crazy abortion laws and all this nutty stuff because Democrats aren’t motivated to vote in these elections. Which is a shame. They should sit there and go, “We should put this much on the agenda during the presidential elections, these many issues to get the people up, and save some for the midterm elections.” You know, gay marriage, marihuana, and things like that should be major issues in the midterms. But they are too worried that they would lose. This election was the lowest attended election in 72 years, which is terrible. The fewer people vote, the more gun lobbyists and psycho-wackos get their stuff passed.

DS: And it’s easy to use fear of black crime, immigration, and so on to get people riled up.

KK: Oh, of course. And many people don’t know that crime has actually gone down. Here’s the thing: the way the Internet is, if there was one murder in a week, that murder would be the thing that gets hyped up completely crazy. Like the ISIS beheadings. If there was no crime in the country all week, everyone would be like, “Oh, my goodness, there are people out there who want to behead us!”

DS: You mentioned the new role of the cop as a soldier in your presentation, and some people are even speaking about the “warrior cop” as a new type of cop, as well as about “militarization as a mindset.” To think of yourself as a warrior cop and put on military riot gear implies that you’re seeing the protesters as enemies, and no longer as citizens with certain rights whom you have sworn to serve and protect.

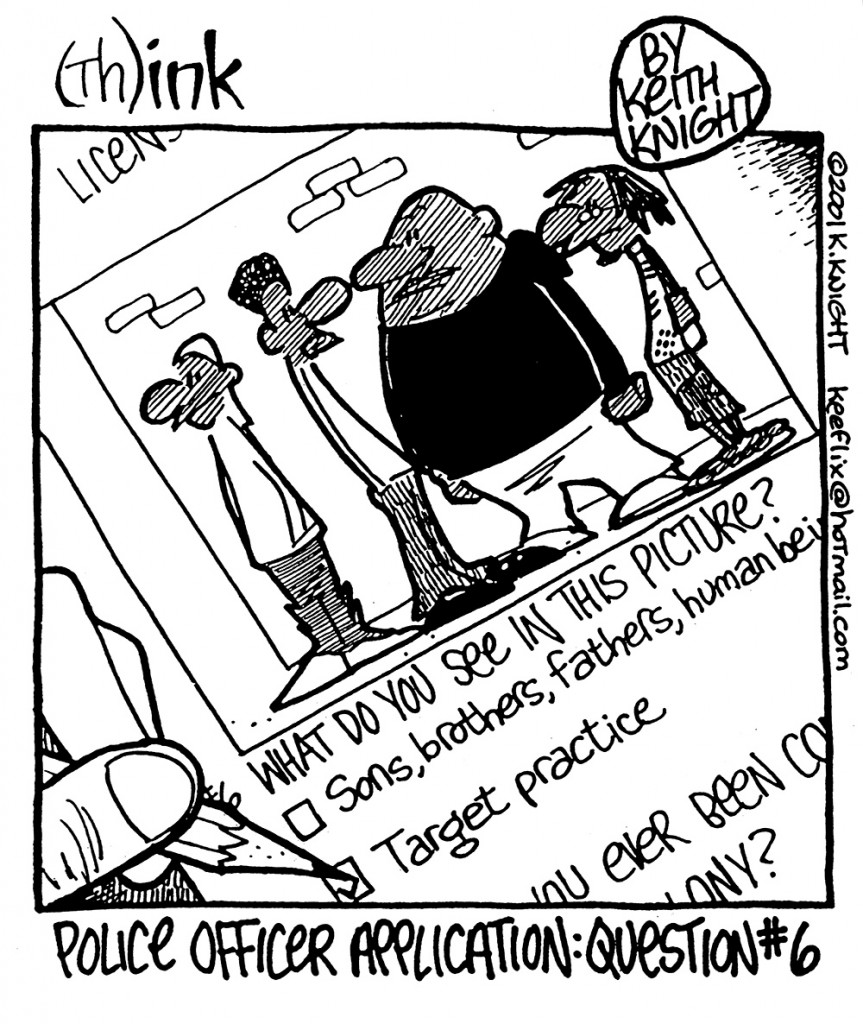

Fig. 2. Keith Knight, (Th)ink, “Target Practice”

KK: I honestly believe that for the Ferguson Police Department to release the information that Michael Brown had been a suspect in a strong-arm robbery shortly before his death and that Darren Wilson had noticed Brown carrying a box of cigars like the one that had been reported stolen, that for them to release that information months later and only then come up with a store surveillance video as proof, it’s a sham, man. They’re just preparing a case, just in case it goes to jury. It’s crazy. It’s not justice, you know. Especially when they move a trial to a region where they know that there’s going to be people who have no issues with the cops, as they’ve done so many times.

DS: That’s the whole idea, right? At least in theory, the people in the jury should reflect the demographics of the community.

KK: Yeah, it should be a jury of your peers. Who’s better to know how these cops behave in these neighborhoods than people from that community?

DS: What do you think about new technologies allegedly being developed right now that would allow the police to prevent people from recording beatings on their cell phones?

KK: It’s definitely something that needs to be fought. That’s all we have: video and sound evidence that allows us to document police brutality. One of the things that they’re trying to do now is to have cameras on their dashboards and uniforms, as well as microphones. But cops are like a virus: they’re adjusting. There are times when they turn them off. Or they will also just say, “Get up off the ground, you’re not complying,” hoping that nobody will get the incident on video. But this recent thing came out when they were just saying that yet the person was completely complying, they beat the hell out of him, and they got caught because somebody videotaped it. I hope that we can still rely on that type of stuff. There are statistics that say that when they started recording the police, the violence went down. You know, there’s a television show in the States called Cops. I used to sit there and watch Cops and go, “Oh my goodness, these are the nicest cops ever.” Maybe we should have people following them with cameras all the time because then they’ll act really nice the whole time. I was watching German cops today where the cops arrested a rich guy at his house. They would never do that in the United States. They’re always just hassling poor people. If they went up on Wall Street and started beating Wall Street bankers, it would go through the roof. It would rival the Super Bowl for viewership. I’d watch it.

DS: How much of this is due to race, and how much of it might be due to class?

KK: It’s a complex thing. It’s a class thing and a race thing. But I’ll tell you this: They won’t move a trial away from a community because poor white people live there. I’ve only seen it happening with black people, as if we were some collective hive where everybody thinks the same. But we’re obviously all individuals. When I was younger, people would always ask me, “How come black people do this or that?” How can you ask me that? We grow up with racial images that are drummed into us, and we need to challenge those. People can change, especially when they see someone speak out on these issues. In order to understand what it’s like to be black in the United States, you have to consider so many things, so much history, and also the effects of popular culture. You know, why does the black guy in the movie always die first? And why, in my world, the black guy always gets the girl, but it never happens in the movies?

Comic Strips and Cartooning

DS: How do you decide whether you want to tackle an issue like police brutality in an autobiographical comic strip like the K Chronicles or in your single-panel political cartoon (TH)ink?

KK: It totally depends on what the angle is I come up with. Or if it’s a one-shot idea or not. I put nothing autobiographical in (TH)ink, so automatically, if it’s my own take, my own little story pertaining to it, then it becomes The K Chronicles. But if it’s more of an outside thing, it becomes (TH)ink. Or it might become The Knight Life if I can use another character in it. That’s the interesting thing about The Knight Life. There is my character, but each one of those other characters is another aspect of me. So there’s a certain thing that my wife fills up, and that’s being the foreigner, or outsider, and also being able to observe America in a different way. And Gunther and Clovis have their own deals. And then the father-son-thing, or being a rapper, or being a black guy that is going to get hassled more. You know that’s my favorite thing, the cop stopping to the dad all the time. Just the idea that that’s a thing to go to all the time, to me, that’s one of the best things about this strip.

DS: Is it difficult for you to find a humorous angle in your comics when you’re dealing with these issues? You’re not really doing any kind of bitter satire. Usually, your comics drive home a very serious point. But as you said during your presentation, you don’t want to be completely destructive or negative but always want to find an upbeat note in it. Is that difficult to find as some things really piss you off?

KK: When you run a bunch of them in a row, then it gets kind of tough. That’s why I vary and change things up a lot. I think there is a fine line between humor and tragedy anyway. I don’t think it’s that hard to find the humor in it. I don’t think everyone can find the humor in it that quickly, though.

DS: How much work by other cartoonists do you look at when you’re approaching an issue? Do you do a lot of research or do you try to block it out in order get an original take on things?

KK: I don’t look at other people’s stuff first, but when I come across great strips, I can admire them. Sometimes you can’t really avoid it. I know what it takes to come up with these ideas. So when you see something golden, you’re just like, “Oh, man!” And when I see something I could very well have come up with, I’m like, “Man, why didn’t I think of that?” And sometimes the styles are completely different, of course.

DS: Could you say a little bit about the creative process behind your work? I’m amazed at how quickly you turn out your cartoons.

KK: First of all, I try to see if I can find an angle from which I can approach the issue that I know other people aren’t going to use. Is there something that I can add to the conversation? And then I sit there and doodle a lot until I come up with something good. Let me tell you about a strip I came up with on the train today. Someone on Facebook said about Pointergate [an incident from November 2014 in which Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges posed for a publicity photo showing her and a black volunteer worker for a nonprofit organization pointing fingers at each other and a television station alleged that they were flashing gang signs]: “Imagine what it must be like to be black and deaf and your ordering French fries, and everybody thinks you’re doing gang sign.’” And I said, “Oh my god, there’s a strip right there. My homework’s done.”

Fig. 3. Keith Knight, The K Chronicles, “How to Discern an Innocent Gesture from a Gang Sign”

DS: How do newspapers approach you when they want a comic strip from you? Do they pick a topic they want you to address?

KK: They mostly give me free room. I’ll get approached by particular editors, say, from medium.com, and they sometimes go, “Hey, we’re looking for something about this or that.” But with my nationally syndicated strip The Knight Life, the editors just get what I do and send it out to newspapers. Unfortunately, there’s a lot of people out there who believe that comics should just make you laugh and nothing else. But I’m never in as many newspapers as I’d like to be. There’s certain things I just can’t ignore. I’m not a guy who’s going to draw a cat who eats lasagna. That’s not my thing. So it can be tough financially. But I’m very of proud of the work I do.

DS: Have you ever been censored or told to avoid a certain topic in your twenty-five-year career in cartooning?

KK: No, not really. I mean, people have sometimes told me not to do certain things, but I always did them anyway. For every newspaper that drops me, I always gain something else. So I never had the feeling that I had to risk it all.

DS: Do you ever get violent threats or hate mail from readers who don’t like your comics?

KK: People who threaten my life generally leave their address on there. I figure if anyone’s goingto take me out, they’re not going to tell me. Whenever I piss off gun advocates, they write stuff like, “You better watch your back.” Also, after 9/11, when I was questioning all of Bush’s crazy bizarre war policies, people went, “You better stop, you better be patriotic!” But eight years of Bush breaking everything we had, that’s going to take years for us to fix and to get into the goodwill of the world again. Speaking of 9/11, earthquakes and collective catastrophes are the only times when we treat each other like we should. Those are the only times when homeless people and rich people help each other the same way. And it lasts for a day or a day-and-a-half, and then people go back to being assholes again. If we could somehow bottle that way of treating each other, it would be an amazing, happy world. I don’t want people to think America is all bad and this totally horrible place. It’s still an almost decent place to live. It’s on its way out, but it’s still pretty cool. But the problem with the police is that they’re really only serving white people. They’re not serving black people. And in order for the country to live up to what it’s supposed to be–you know, liberty and justice for all–it’s America’s problem, even though a lot of people say it’s a black problem.

Looking Forward, Making Change

DS: Has your perspective on the US changed since you’ve been married to a German wife and maybe also since you’ve become a father? Has the outside perspective made you reevaluate what it means, for you, to be an American? Last night in the Q & A after your presentation, a black girl in the audience asked you about whether you would encourage her to move to the US because she was so concerned over the whole issue of police brutality.

KK: That question and also the question “Why don’t you leave the United States?” really affect me. I have to give more of an argument for why I should stay in the United States. It’s my home, and we need to make change. You don’t just be like, “This place is a mess, I’m out of here!” I would like to put in some years here [in Germany], but not because I’m trying to get away from police brutality or maybe another Bush getting into the White House. But yes, I think your perspective does change when you get married. You have another person around who has her own views. What I really like about Kerstin’s perspective, being German, is the whole WWII thing. In Germany, you learn what happened in WWII. You learn that you were the bad guys, that it was terrible, and that it shouldn’t happen again. Whereas in the United States, when you hear about slavery, it’s often pushed off as something that happened so long ago. There are books that saythings like “a lot of the slave owners treated their slaves like family.” But it was actually completely effed up: They broke up families, and when, supposedly, the slaves were freed, they weren’t really freed. Because no one was giving them equal pay and good housing. And there were all the Jim Crow laws that said “separate but equal,” but you know, whites had pluming and there was abucket for black people. There were lynchings up until the 1960s, and the American government was experimenting on black people into the 1970s until someone called them out on it. It was not that long ago when I could be lynched, and then it could be made into a postcard, and people could send it around, saying, “Yay, this just happened in our backyard,” with the U.S. Postal Service saying, “Yeah, we’ll send this stuff around.” In addition, in some neighborhoods, blacks couldn’t be rented to, and they couldn’t own houses. Black people couldn’t own shit until the Seventies. There were under-the-radar laws that you couldn’t rent to black and Jews. Once you learn that aspect of it and see the white privilege behind the accumulation of wealth, you understand why 40 years of affirmative action are not going to change hundreds of years of what went on. And it still goes on with drug laws and similar stuff, so don’t think it’s all over now and everything is wonderful and hunky dory. That’s not the case. And I always make the argument that white women have benefited most from affirmative action.

DS: What will you be teaching your kids about America and about the world around you?

KK: I will pass on several decades’ worth of comic strips and cartoons. So they will get an idea of their dad’s take on life. And what they will learn is: talk to strangers–not the guy in a raincoat with no pants on at a bus stop, obviously–but reach out to people you wouldn’t normally interact with. Travel is the best education you could possibly get. Listen to people’s stories. A lot of my comics come from the stories I hear from people. You’ve got to know: I write about everything, and I’m basically known as a very optimistic cartoonist, so my stuff on police brutality and racial discrimination is just a small, and somewhat depressing, slice of what I do. All I can do is hope that my kids take what I’ve created and understand. One of the things we’ve got to do is get the hell out of LA. It’s not the greatest place to raise kids.

DS: Do you think anything positive might come out of Ferguson, now that they decided not to have a trial?

KK: Well, at least people have police brutality much more on their radars now. It’s not in the government’s or the police’s best interest to let people know how often this happens. And this happens probably once every forty-eight hours. We just hear the most high profile stuff. In the last few days, a twelve-year old with a plastic gun was killed in Cleveland, and then a guy in New York was shot coming out of a dark stairwell. I’m just hoping that people keep putting these things up and letting others know what’s going on. It’s a serious problem, and it’s not just black and brown people either. But if things go back to being quiet, they’re not going to do anything about it. That’s why these protests still need to go on. That’s why I still need to draw dark cartoons.

For more on Keith Knight’s comics and activities, go to www.kchronicles.com and http://www.knightlifecomic.com.

Daniel Stein is professor of North American Literary and Cultural Studies at the University of Siegen. He is the co-editor of Transnational Perspectives on Graphic Narratives: Comics at the Crossroads (Bloomsbury 2013) and From Comic Strips to Graphic Novels: Contributions to the Theory and History of Graphic Narrative (De Gruyter 2013).

[…] was proud to publish Daniel Stein’s conversation with American cartoonist Keith Knight (in English), creator of The K Chronicles, (Th)ink, and The Knight Life, “About Comics and Police […]