Annual Conferences

Since 2006, ComFor organizes annual academic conferences on various topics within the field of comics research.

|

19th annual conference, October 2024: Graphic Medicine (Groningen) |

|

18th annual conference, December 2023: Was war, ist, wird Comicforschung – für uns? (Gleichen) |

|

17th annual conference, November 2022: Labor and class conditions in comics (Dortmund) Call for Papers |

|

16th annual conference, October 2021: Coherence in Comics: An Interdisciplinary Approach (Salzburg) |

|

15th annual conference, October 2020: Comics and Agency – Actors, Publics, Participation (Tübingen) Call for Papers |

|

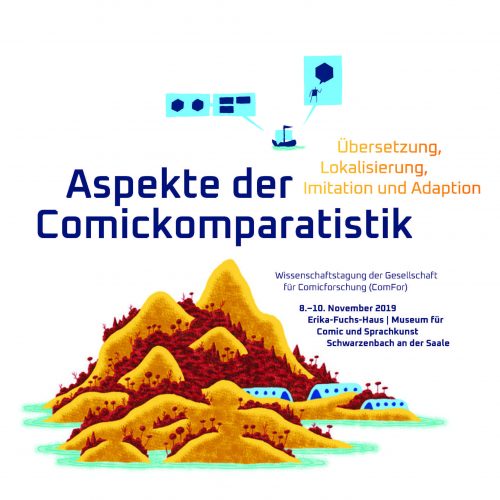

14th annual conference, November 2019: Translation, Localisation, Imitation, and Adaptation: Comparative Aspects in Comics Studies (Schwarzenbach a.d. Saale) |

|

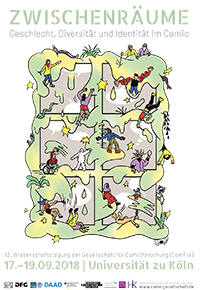

13th annual conference, September 2018: Spaces Between – Gender, Diversity and Identity in Comics (Cologne) Call for Papers |

|

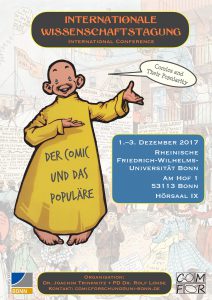

12th annual conference, December 2017: Comics and their Popularity (Bonn) |

|

11th annual conference, November 2016: Comics in der Schule – Schule im Comic [Comics in Schools – School in Comics] (Essen) Call for Papers (German) |

|

10th annual conference, September 2015: History in Comics – History of Comics (Frankfurt/Main) Call for Papers |

|

9th annual conference, September 2014: Drawing Borders, Crossing Boundaries (Berlin) |

|

8th annual conference, November 2013: Comics and the Natural Sciences (Erlangen) Call for Papers |

|

7th annual conference, September 2012: Comics and Politics (Freiburg) Call for Papers |

|

6th annual conference, November 2011: Reportagecomics. Dokumentarische Comics. Comicbiographien [Documentary Comics: Journalism and Biography] (Passau) |

| 5th annual conference, November 2010: Bilder des Comics – Visualität, Sequenzialität, Medialität [Pictures of Comics: Visuality, Sequentiality, Mediality] (Gießen) Program |

|

|

4th annual conference, November 2009: Erzählen im Comic [Narration in Comics] (Köln) |

| 3rd annual conference, November 2008: Der Comic als Gegenstand der Kultur- und Sozialwissenschaften [Comics as a Subject of Cultural and Social Studies] (Koblenz) |

|

| 2nd annual conference, November 2007: Comicforschung als interdisziplinäre Aufgabe [Comic Studies as an Interdisciplinary Task] (Koblenz) |

|

|

1st conference, November 2006: Forschungsberichte zu Struktur und Geschichte der Comics in Deutschland [Research Reports on the Structure and History of Comics in Germany] (Koblenz) Program Conference Proceedings |

18th ComFor Annual Conference 2023: „What was, is, becomes comics studies – for us?“

From December 11-13, 2023, the 18th annual conference of the Society for Comics Studies (ComFor) will take place at the Stiftung Akademie Waldschlösschen in 37130 Gleichen. The event will be organized by Christina Meyer, Vanessa Ossa, and Lukas R.A. Wilde.

From December 11-13, 2023, the 18th annual conference of the Society for Comics Studies (ComFor) will take place at the Stiftung Akademie Waldschlösschen in 37130 Gleichen. The event will be organized by Christina Meyer, Vanessa Ossa, and Lukas R.A. Wilde.

On the occasion of ComFor’s upcoming tenth anniversary as a registered association, this timespan will be subject to a critical reflection: How has comics studies developed and changed over the past ten years? Which recurring, but also new questions and research perspectives have we been dealing with since 2014? Which disciplinary shortcomings or desiderata do we need to address more precisely together in the future? „What was, is, becomes comics studies – for us?“ quite literally addresses our institution as well as the biographically shaped perspectives of our participating members.

Individual seats to participate in the lectures and panel discussions are still available, inquiries can be sent informally to vorstand@comicgesellschaft.de.

Program of the ComFor Annual Conference 2021: “Coherence in Comics”

The ComFor web editorial team is back from its summer break with an announcement on its own behalf: the 16th annual conference of the German Society for Comics Studies (ComFor) will take place from 14-16 October 2021!

The ComFor web editorial team is back from its summer break with an announcement on its own behalf: the 16th annual conference of the German Society for Comics Studies (ComFor) will take place from 14-16 October 2021!

Announcement:

“The 16th Annual Conference of the German Society for Comics Studies (ComFor) approaches the topic “Coherence in Comics” from an interdisciplinary perspective. We seek to not only negotiate and explain meaning-making across panel borders and semiotic modes, but also across disciplines, seeking commonalities, shared interests and points of contact. […] We are looking forward to keynotes by Janina Wildfeuer, Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication and Information Studies at the University of Groningen, Barbara Postema, author of Narrative Structure in Comics: Making Sense of Fragments, and Charles Forceville, Associate Professor at the University of Amsterdam (Department of Media Studies). Apart from the conference’s central focus on coherence, ComFor aims to promote interdisciplinary cooperation and dialogue across all areas of comics research. The 16th Annual Conference will therefore continue the tradition of an open workshop format that allows researchers to present and gather feedback on various projects within comics studies, without any thematic restrictions. We are also excited to announce a comic reading (in German) by Vina Yun as part of this year’s program, arranged by the Austrian Comics Society (OeGeC – Österreichische Gesellschaft für Comic-Forschung und -Vermittlung).”

Registration:

The conference will be held online via WebEx; there is no conference fee; registration by email to comfor2021@sbg.ac.at is requested.

Organisators:

- Elisabeth Krieber (Universität Salzburg)

- Markus Oppolzer (Universität Salzburg)

- Hartmut Stöckl (Universität Salzburg)

Programme:

Thursday, 14 Oct., 2021

10:30 – 11:30 – Members’ Meeting of the Society for Comics Studies (ComFor) (in German)

11:30 – 13:00 – Lunch Break

13:00 – 13:15 – Conference Opening

13:15 – 14:15 – OPEN FORUM I

Mihaela Precup and Dragoș Manea – “The Overfamiliar Perpetrator: Hipster Hitler, Transcultural Memory, and the Banalisation of Genocide”

Pedro Réquio – “Revolutionary Comics/Revolutionary Politics: Portugal in the 1970’s”

14:15 – 14:45 – Break

14:45 – 15:45 – OPEN FORUM II

Ahlam Almohissen – “Multimodal Humour in Cartoons: Social Semiotic Perspective”

Xiaolan Wei – “Coherence Constructed through Comics and Spoken Language in Chinese College Students’ Five Minutes English Academic Speech”

15:45 – 16:15 – Break

16:15 – 17:30 – KEYNOTE Janina Wildfeuer

“Demystifying the Magic. A Multimodal Linguistic Approach to Coherence in Visual Narratives”

17:30– 18:00 – Break

18:00 – 19:00 – AWARD CEREMONY

Martin-Schüwer-Publication Prize 2021 for Excellence in Comic Studies

Friday, 15 Oct., 2021

09:00 – 10:30 – PANEL 1: FORMS AND AESTHETICS OF COHERENCE (Panel Chair: Stephan Packard)

Elisabeth El Refaie – “A Tripartite Classification of Visual Metaphor as a Basis for Studying Coherence in Comics”

Martin Foret – “‘Like a Speech’ or Searching for Coherence between Codes Used in Comics: The Interplay of Various Codes within the Specific Complex Code (or Better Meta-Code) of Comics”

Lukas R.A.Wilde – “Essayistic Comics: Non-narrative Coherence and Pictogrammatics with Schlogger, Sousanis, Barry”

10:30 – 11:00 – Break

11:00 – 12:30 – PANEL 2: COHESION IN COMICS: MULTIMODAL AND PRAGMATICIST APPROACHES (Panel Chair: Janina Wildfeuer)

Chiao-I Tseng – “Structures of Cohesion in Comics”

John Bateman – “Nonlinear Coherence? Steps Beyond the Sequence in Sequential Art”

Stephan Packard – “Cohesion in Panel Graphs: A Psychosemiotic Approach”

12:30 – 14:00 – Lunch Break

14:00 – 15:30 – PANEL 3: IN(COHERENT) SPACES AND NARRATORS (Panel Chair: Mihaela Precup)

Barbara Margarethe Eggert – “Comics as Coherence Machines? Exemplary Observations on the Functional Spectrum of Museum Comics”

Martha Kuhlman -“Comics and the Miniature: Thinking Inside the Box”

Elizabeth Allyn Woock – “The Graphic ‘I’ in Academic Comics”

15:30 – 16:00 – Break

16:00 – 17:15 – KEYNOTE: Charles Forceville: “Visual and Multimodal (Meta)Representation of Speech, Thought, and Sensory Perception in Comics”

17:15 – 17:30 – Break

17:30 – 19:00 – COMIC READING (in German)

presented by the Austrian Comics Society (OeGeC Österreichische Gesellschaft für Comic-Forschung und -Vermittlung)

Vina Yun: Homestories

Saturday, 16 Oct., 2021

09:00 – 11:00 – PANEL 4: Linguistic and Cognitive Approaches to the Visual Language of Comics (Panel Chair: Neil Cohn)

Neil Cohn – “Grammar of the Visual Language of Comics”

Irmak Hacımusaoğlu – “What Are Motion Lines Anyways?”

Bien Klomberg – “Calvin the Elephant: Resolving Discontinuity through Conceptual Blends”

Lenneke Lichtenberg – “Understanding Lightbulb Moments in Comics: The Processing of Visual Metaphors that Float above Characters’ Heads”

11:00 – 11:30 – Break

11:30 – 12:45 – KEYNOTE Barbara Postema – “Narrative Structure in Wordless Comics”

12:45 – 14:30 – Lunch Break

14:30 – 16:00 – PANEL 5: FRACTURED BODIES AND IDENTITIES (Panel Chair: Barbara Margarete Eggert)

Tina Helbig – “Frames as Skin and Comic Book Pages as a Fractured Bodies in Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman and in Emily Carroll’s Short Horror Comics”

Carolina González Alvarado – “A Perverse Beauty and the Mechanisms of Control over the Body: An Analysis of Helter Skelter by Kyoho Okazaki”

Rita Maricocchi – “(In)coherencies in the Manifestations of German Identity in Birgit Weyhe’s Madgermanes”

16:00 – 16:30 – Break

16:30 – 18:00 – PANEL 6: COHERENCE IN SUPERHERO NARRATIVES: THE CHALLENGES OF SERIALIZATION AND WORLD-BUILDING (Panel Chair: Lukas R.A. Wilde)

Mark Hibbett – “Image Quotation of Past Events to Enforce Storyworld Cohesion in John Byrne’s Fantastic Four”

Amadeo Gandolfo – “Do the Collapse: Final Crisis and the Impossible Coherence of the Superhero Crossover”

Scott Jordan and Victor Dandridge Jr. – “Invincible: The Many Shapes, Forms, and Sizes of Coherence through Comics”

18:00 – 18:15 – Conference Closing

Further information and a detailed programme can be found on Event website.

CFP: Coherence in Comics: An Interdisciplinary Approach

Schedule for the Annual ComFor Conference 2020: „Comics & Agency“

15th Annual Conference of the German Society for Comic Studies:

15th Annual Conference of the German Society for Comic Studies:

Comics & Agency: Actors, Publics, Participation

Online | Live via Zoom

Registration:

There is no conference fee, but in order to participate you will need to register by sending an email to comfor@comicgesellschaft.de no later than 5 October 2020.

Organisers:

Vanessa Ossa (University of Cologne)

Jan-Noël Thon (Norwegian University of Science and Technology)

Lukas R. A. Wilde (University of Tuebingen)

Schedule:

| Thursday, 8 October 2020 | |

| 13:30 CEST | Welcome and Introduction: Christina Meyer (Free University Berlin), Vanessa Ossa (University of Cologne), Jan-Noël Thon (Norwegian University of Science and Technology), Lukas R. A. Wilde (University of Tuebingen) |

| Panel 1: Digital Agency | |

| 14:00 CEST |

|

| 15:30 CEST | Coffee Break |

| Panel 2: Intermedial Agency | |

| 16:00 CEST |

|

| 17:30 CEST | Coffee Break |

| Keynote 1 | |

| 18:00 CEST | Henry Jenkins (University of Southern California): Comics and Stuff |

| Award Ceremony: Martin-Schüwer-Preis 2020 | |

| 20:00 CEST | Dorothee Marx (University of Kiel), Daniel Stein (University of Siegen), and the Winner of the Martin-Schüwer-Preis |

| Friday, 9 October 2020 | |

| Panel 3: Authorial Agency | |

| 11:30 CEST |

|

| 13:00 CEST |

Lunch Break |

| Panel 4: Editorial Agency | |

| 14:00 CEST |

|

| 15:30 CEST | Coffee Break |

| Panel 5: Distributional Agency | |

| 16:00 CEST |

|

| 17:30 CEST | Coffee Break |

| Keynote 2 |

|

| 18:00 CEST | Mel Gibson (Northumbria University): Librarians, Agency, Young People, and Comics: Graphic Account and the Development of Graphic Novel Collections in Public Libraries in Britain in the 1990s |

| Virtual Comic Museum Erlangen | |

| 20:00 CEST | Lisa Neun and Ralf Marczinczik |

| Saturday, 10 October 2020 | |

| Open Forum | |

| 11:30 CEST |

|

| 13:00 CEST |

Lunch Break |

| Panel 7: Fan Agency (Part I) | |

| 14:00 CEST |

|

| 15:30 CEST | Coffee Break |

| Panel 8: Fan Agency (Part II) | |

| 16:00 CEST |

|

| 17:30 CEST | Coffee Break |

| Concluding Discussion: Where Do We Go from Here? | |

| 18:00 CEST | Vanessa Ossa (University of Cologne), Jan-Noël Thon (Norwegian University of Science and Technology), Lukas R. A. Wilde (University of Tuebingen) |

Download schedule as PDF file.

CFP Update – Going Online | Deadline Extended: Comics and Agency – Actors, Publics, Participation (15th Annual Conference of the German Society for Comics Studies)

Program of the Annual ComFor Conference 2019: “Comparative Aspects in Comics Studies”

14. Annual Conference of the Society for Comics Studies (ComFor):

Translation, Localisation, Imitation, and Adaptation: Comparative Aspects in Comics Studies

Program

D| Talk or panel in German

E| Talk or panel in English

| Freitag | Friday | |

| 11.30 am | D| Member’s meeting of the Society for Comics Studies (ComFor) |

| 1.00 pm | Mittagspause | Lunch Break (Snacks) |

| Offenes Forum I | Open Forum I | |

| 1.30 pm | D| Lukas Etter:

»It’s a relief« Aline Kominsky-Crumbs spielerische Imitation und Subversion von Stildiskursen |

| 2.00 pm | D| Marie Müller:

Prudhommes Adaption von Struths Museum Photographs |

| 2.30 pm | E| Jennifer Neidhardt:

»I knew there was something in the closet«: Marvel’s Spider-Man and Queer Identity |

| 3.00 pm | Pause | Break |

| Offenes Forum II | Open Forum II | |

| 3.15 pm | E| Katharina Serles and Marina Rauchenbacher:

Visualities of Gender in German-language Comics |

| 3.45 pm | E| Jeff Thoss, Ian Hague, Ian Horton, and Sylvia Kesper-Biermann:

Lost in Translation: Connecting English-language and German-language Comics Studies |

| 4.15 pm | E| Ivan Petrovic:

Translating Comics between Cultures and within Languages: The Case of Yugoslavian Comics in German-Speaking Countries |

| 4.45 pm | Pause | Break |

| 5.00 pm | Begrüßung | Commencement |

| D| Panel I: Comic-Übersetzung und ihre populäre Vermittlung | |

| 5.15 pm | Alexandra Hentschel (Schwarzenbach):

Das einzige Museum für Comic-Übersetzung |

| 5.45 pm | Nassrin Sadeghi (Dortmund):

comic+cartoon. Pläne zum neuen Schauraum für Comic-Kunst in Dortmund |

| 6.15 pm | Pause | Break |

| E| Keynote I: Practice in Translation | |

| 6.30 pm | David Zane Mairowitz (Berlin): KafKa in KomiKs |

| 8.00 pm | Abendessen | Dinner (Buffet) |

| Samstag | Saturday | |

| E| Keynote II: International Perspectives on Comics Translation | |

| 9.00 am | Federico Zanettin (Perugia):

New Methods in Examining Comics in Translation |

| 10.15 am | Pause | Break |

| E| Panel II: Translation and Localisation | |

| 10.30 am | Laura Antola (Turku):

»If the other Nordic countries wish to publish rubbish, they can go ahead!« Transnational strategies for adapting the Marvel Universe in Finland |

| 11.15 am | Romain Becker (Lyon):

»Just according to keikaku (keikaku means plan)«:How fans translate (or don’t) |

| 12.00 noon | Pause | Break |

| 12.15 pm | Keren Zdafee (Tel Aviv):

Egyptianizing Mickey and Minnie? On cultural transfers and the domestication of Western imagery in the Egyptian satirical press of the 1930s |

| 1.00 pm | Lynn L. Wolff (Michigan):

Translation, Modification, Visualization: Comparative Aspects of Nora Krug’s Heimat |

| 1.45 pm | Mittagspause | Lunch Break |

| E| Panel III: Intermedia Adaptation | |

| 3.00 pm | Olga Kopylova (Sendai):

Lines and Layers, Look and Feel: Transformations of style in manga-to-anime adaptations |

| 3.45 pm | Elisabeth Krieber (Salzburg):

Adapting the Queer Autographic Self: Fun Home from the Comics Page to the Broadway Stage |

| 4.30 pm | Pause | Break |

| 4.45 pm | Marina Rauchenbacher (Wien):

Who (and where) is Alice? Anke Feuchtenberger’s Adaptation of Lewis Carroll’s Alice |

| 5.30 pm | Pause | Break |

| 6.00 pm | Preisverleihung & Preisvortrag | Award & Special Keynote

Martin-Schüwer-Publikationspreis für herausragende Comicforschung Martin Schüwer Publication Award for Excellence in Comics Studies |

| 7.00 pm | Conference Dinner |

| Sonntag | Sunday | |

| D| Keynote III: Kulturwissenschaftliche Translatologie | |

| 9.00 am | Natalie Mälzer (Hildesheim):

Comic-Übersetzungen und Adaptionen als kulturelle Praxis |

| 10.15 am | Pause | Break |

| D| Panel IV: Übersetzungen und Lokalisierungen | |

| 10.30 am | Christine Hermann (Wien):

Die vielen Namen von Suske und Wiske. Ein flämischer Abenteuercomic in deutscher Übersetzung |

| 11.15 am | Yun-Jou Chen (Taiwan/Mainz):

»Popalania, the perfect country« Neue Überlegungen zu dem Fall der Popeye-Übersetzung (1967-1968) in Taiwan |

| 12.00 noon | Pause | Break |

| D| Panel V: Intermediale Adaptionen | |

| 12.15 pm | Dietrich Grünewald (Koblenz/Reiskirchen):

Die Kunst der Adaption – Oscar Wilde: Das Bildnis des Dorian Gray |

| 1.00 pm | Linda-Rabea Heyden (Jena/Berlin):

Klassikeradaption im Comic funktional und medial, am Beispiel von Goethes Faust |

| 1.45 pm | Mittagspause | Lunch Break

& Treffen der AG Diversity | Meeting of the Committee for Diversity |

| 3.00 | Markus Oppolzer (Salzburg):

Nachgezeichnete Leben:Die Künstlerbiografie am Beispiel Vincent van Goghs |

| 3.45 pm | Véronique Sina (Köln):

Queering Comic and Film: Coming out und coming of age in Le Bleu est une couleur chaude (2010) und LA VIE D’ADÈLE (2013) |

| 4.30 pm | Pause | Break |

| D| Panel VI: Noch einmal: Vergleichen | |

| 4.45 pm | Jörn Ahrens (Gießen):

Die Erfindung des Comic in Deutschland. Frühe Perspektiven der Comicforschung |

| 5.30 pm | Ole Frahm (Frankfurt am Main): Phantom. Phantomias. |

| 6.15 pm | Abschlussdiskussion | Conclusion |

| ~7.00 pm | Abreise | Departure |

Organisers:

Christian Bachmann, Juliane Blank, Alexandra Hentschel and Stephan Packard

See also:

Registration

Accomodation

Directions

CFP: Translation, Localisation, Imitation, and Adaptation

Conference Report: ComFor Annual Conference 2018

A Conference Report by J. Rehse, P. Zwirner, M. Pollich, Y. Neuhaus, S. Böhm, and L. Respondek (students of the University of Cologne), Photography by Philin Zwirner

From September 17th to 19th 2018 the 13th Annual Conference of the German Society for Comics Studies (ComFor) took place at the University of Cologne. Under the main theme “Spaces Between – Gender, Diversity and Identity in Comics” the conference schedule – planned and organized by Véronique Sina and Nina Heindl – offered a wide range of interesting insights into state-of-the-art research on the nexus between the medium of comics and categories of difference and identity such as gender, dis/ability, age, and ethnicity. Participants who already arrived on Sunday (the day before the official start of the conference) had the opportunity to become familiar with the city of Cologne. In the afternoon, the cultural program started with a guided tour through the exhibition “Avengers Assemble” held at the Cöln Comic Haus. With highly entertaining host(s) and a lot of interesting details, the visit of the exhibition was a perfect start for the conference. Afterwards, the group took a stroll along the Rhine in warm and shiny weather. With a boat-trip along the picturesque panorama of the most beautiful part of Cologne, the pre-program ended and gave the participants the opportunity to enjoy the rest of the evening in the historic center of Cologne.

At the official beginning of the conference on Monday, the conveners Véronique Sina and Nina Heindl, as well as Manuela Günter (Vice-Rector for Gender Equality and Diversity of the University of Cologne), and Stephan Packard (President of the German Society for Comics Studies) welcomed all speakers and guests. They stressed that it is their great pleasure to open a conference that not only focuses entirely on gender, diversity, and identity in comics, but also presents a majority of female speakers as well as an all-female organizational team – a premiere for the German Society for Comics Studies.

At the official beginning of the conference on Monday, the conveners Véronique Sina and Nina Heindl, as well as Manuela Günter (Vice-Rector for Gender Equality and Diversity of the University of Cologne), and Stephan Packard (President of the German Society for Comics Studies) welcomed all speakers and guests. They stressed that it is their great pleasure to open a conference that not only focuses entirely on gender, diversity, and identity in comics, but also presents a majority of female speakers as well as an all-female organizational team – a premiere for the German Society for Comics Studies.

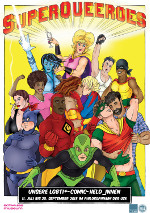

Exhibition Poster and Program Flyers for ComFor 2018

In less than two and a half months, ComFor’s Annual Conference 2018 will take place at the University of Cologne on the topic “Spaces Between – Gender, Diversity and Identity in Comics”. At the same time one can visit the exhibition “SuperQueeroes. Unsere LGBTI*-Comic-Held_innen”, which was designed in 2016 by the Schwules Museum Berlin and shown with great success. For the first time, queer comic heroes of various kinds were thematized in the German museum world. As part of the ComFor annual conference, the exhibition was brought to Cologne under the organization of Christine Gundermann and reworked for the university by students as part of a seminar.

In less than two and a half months, ComFor’s Annual Conference 2018 will take place at the University of Cologne on the topic “Spaces Between – Gender, Diversity and Identity in Comics”. At the same time one can visit the exhibition “SuperQueeroes. Unsere LGBTI*-Comic-Held_innen”, which was designed in 2016 by the Schwules Museum Berlin and shown with great success. For the first time, queer comic heroes of various kinds were thematized in the German museum world. As part of the ComFor annual conference, the exhibition was brought to Cologne under the organization of Christine Gundermann and reworked for the university by students as part of a seminar.  The exhibition can be visited from 11 July to September 20 in the foyer of the Philosophikum of the University of Cologne. Vernissage is on the 11th of July from 12 o’clock, opening with a talk by and about comic artist Ralf König . Subsequently, the exhibition will be opened by Dr. Kevin Clarke, curator of the Schwules Museum Berlin.

The exhibition can be visited from 11 July to September 20 in the foyer of the Philosophikum of the University of Cologne. Vernissage is on the 11th of July from 12 o’clock, opening with a talk by and about comic artist Ralf König . Subsequently, the exhibition will be opened by Dr. Kevin Clarke, curator of the Schwules Museum Berlin.

The organizers of the conference, Véronique Sina and Nina Heindl, have now also published digital program flyers in German and English (design: Julia Eckel), which not only provide quick overviews of the topics and the schedule of the conference, but – with motifs by artist Aisha Franz – also turned out to be very appealing:

Program flyer in German

Program flyer in English

Continue to the conference’s page with information on the registration process